Stolby, Stolby

Alexander Berman

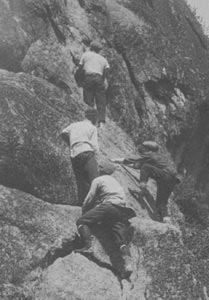

When climbing a rock alone without a rope any error could be fatal. When climbing a rock alone without a rope any error could be fatal.

I always climbed rocks on Stolby in company with those who had each

stone at their fingertips. They taught me how to use a tiniest notch in

the rock and showed well-tried movements to be imitated precisely at

complicated pieces of routes.

I think of my first experience with Stolby as I was hanging on the even

wall of Mitre over sixty metres of precipice. Listening to advises from

above of how to place my hand I suddenly imagined my foot slipping, and

then came the fear and a sharp feeling of loneliness.

It was later, at a higher and still harder route, reasonably called

Hallelujah, that I appreciated the magic bonds of human voice, no less

tangible and solid than a rope. To surmount this piece, one should lean

with his right hand on a half-palm slanting ledge, pull himself up, fold

himself like a pen-knife, and place the leg onto that shelf. Meanwhile the

left hand should go up to catch a groove above. And it failed! Balancing

in this unstable position I suddenly felt the wall swaying. The confidence

returned the very next moment, as if I caught a rope; I stretched harder

and reached the hold. And only after I had stood up and looked around

taking a deep breath, I realised the endearing whisper I heard a second

before: ‘A little more, a little, just a bit… That’s it!’

That summer I came to Stolby once again to relieve the acute feeling of

risk while “free climbing” without a rope. It was Sunday and thus all

crowded. In vain I tried to find my friends, Daddy Karlo, Dick, Gapon (stolbists

always use nicknames, so we are often unaware of their real names). None

of them came to Stolby that morning, but I met two other young guys, Grey

and Artist.

We climbed together up First Pillar along the easiest and the most

popular route called the Rolls. Grey was far ahead. He often stepped off

the way into more difficult paths, and kept talking - ‘The stone looks

smooth, but actually it is rough and porous. Push yourself up and go…

Don’t press yourself to the rock, stand up strait …’ He ran up a

steep rock and a second later was already five meters above me. - ‘We

used to think it was a top flight until we dared to try it once ourselves.

Come on, try!’ - I did and ran up the reddish rock, pushing myself hard

with every step, and took a sit next to Grey. We climbed together up First Pillar along the easiest and the most

popular route called the Rolls. Grey was far ahead. He often stepped off

the way into more difficult paths, and kept talking - ‘The stone looks

smooth, but actually it is rough and porous. Push yourself up and go…

Don’t press yourself to the rock, stand up strait …’ He ran up a

steep rock and a second later was already five meters above me. - ‘We

used to think it was a top flight until we dared to try it once ourselves.

Come on, try!’ - I did and ran up the reddish rock, pushing myself hard

with every step, and took a sit next to Grey.

A Sunday stream of people was flowing by, some outrunning, others

jumping. A girl stopped, lost her balance and her arm was about slipping

off. A young man nearby pressed it to the rock and pushed the girl

slightly up, then bent himself and jumped aside to keep his own balance.

Another girl was speaking to somebody below and, unwillingly, was

approaching the edge to see her partner. Grey interrupted his story, -

‘Hey, 're you, eager to fall?’ - ‘No, I am holding tight!’ -

‘Everyone would think the same.’

The route is so easy that it's hard to tell a skilled climber from a

beginner. There was a time when stolbists used to wear a uniform -

embroidered waistcoats, decorated fezzes, wide trousers, sashes (red, blue,

yellow), and galoshes. A sash was not a mere matter of garment. This strip

of satin, up to ten metres long, wound around the waist could be used as a

rope. Sashes and galoshes were common, but few climbers wore the complete

uniforms, with waistcoats and fezzes. To wear the uniform one had to learn

climbing for years, as it meant an obligation to take the hardest and most

dangerous ways, either to prove being in the caste or to save anyone

helplessly hanging on the rock, as it often happens on crowded pillars. To

wear an unmerited uniform was equivalent to shame or suicide. It was a

free-will garment of high virtue. However, the local authorities fighting

against yoots simply prohibited the waistcoats, the sashes, and the fezzes

not looking very much into the origin of the unusual clothes. Old

stolbists don't like to talk about it, ’Never mind the uniform, Stolby

are still there.’ The route is so easy that it's hard to tell a skilled climber from a

beginner. There was a time when stolbists used to wear a uniform -

embroidered waistcoats, decorated fezzes, wide trousers, sashes (red, blue,

yellow), and galoshes. A sash was not a mere matter of garment. This strip

of satin, up to ten metres long, wound around the waist could be used as a

rope. Sashes and galoshes were common, but few climbers wore the complete

uniforms, with waistcoats and fezzes. To wear the uniform one had to learn

climbing for years, as it meant an obligation to take the hardest and most

dangerous ways, either to prove being in the caste or to save anyone

helplessly hanging on the rock, as it often happens on crowded pillars. To

wear an unmerited uniform was equivalent to shame or suicide. It was a

free-will garment of high virtue. However, the local authorities fighting

against yoots simply prohibited the waistcoats, the sashes, and the fezzes

not looking very much into the origin of the unusual clothes. Old

stolbists don't like to talk about it, ’Never mind the uniform, Stolby

are still there.’

A boy daringly jumped down from somewhere onto the narrow ledge next to

us. A girl was slowly following him facing the rock. The guy greeted Grey

and showed him one of his galosh, - "I've worn it through since

morning!" The galosh was examined closely. Meanwhile the girl, who

kept coming down silently, was already close to us but scared to jump. She

bent her knees, squatted (tight jeans, metal rivets on the hip-pockets)

and jumped down keeping hardly her balance. The guy, continuing his galosh

story, braced up but didn’t give his hand. The girl (bleached blond, big

painted eyes) looked at him angrily "Why, you?!" And the

discussion about went on.

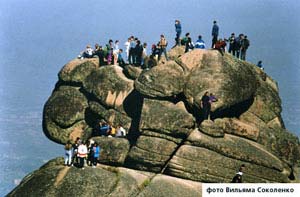

"I love First Pillar", - says Grey. - "It's always

crowded. The paths are blocked up, but those in a hurry climb on the

fringe. One finds the way, the others follow him. What tricks they play!

There are thousands of paths here! Each encourages to prove yourself and

to watch the others thus mixing 'business with pleasure'. Once many guys

gathered here. What a climbing it was! One would need five years to repeat

that! It was then that San'ka climbed head over heels". - "Is he

really good at walking head first?" - "No, not very, but he

upped and did it. Few have been able to repeat that". "I love First Pillar", - says Grey. - "It's always

crowded. The paths are blocked up, but those in a hurry climb on the

fringe. One finds the way, the others follow him. What tricks they play!

There are thousands of paths here! Each encourages to prove yourself and

to watch the others thus mixing 'business with pleasure'. Once many guys

gathered here. What a climbing it was! One would need five years to repeat

that! It was then that San'ka climbed head over heels". - "Is he

really good at walking head first?" - "No, not very, but he

upped and did it. Few have been able to repeat that".

I could never catch when his stories graded into illustrations. And

that time again - scarcely I tried to protest, he was already setting off,

head first, down the steep rock, and I could only see his galoshes, his

long neck, his open arms, and fingers spread apart. Some coins dropped

from his pockets, rolled jingling and silently disappeared in a precipice.

Several coins got stuck in the cracks, and Grey, laughing, still head

first, tried to pick them. Then he climbed up and joined me, but at that

moment Artist ventured into the BIF crest (a very dangerous route

discovered by Belyak Ivan Filippovitch, a teacher). A cigarette in his

mouth, Artist easily covered the first part of the route, but suddenly

stopped not far from us. He was palpating the stone, threw away his

cigarette, raised his elbows trying to relax. - "There's hardly a

chance to get out", - Grey said. While sitting comfortably on our

stone, we could see Artist three metres far from us, relaxing his arms,

breathing deeply. Grey was waiting anxiously. Finally Artist found some

handholds, clambered over the stone, sat down and asked, - "If one's

hands shake, is it from fear or from tension?’

I was following Grey up First Pillar along the route called Question.

The "question" is whether you jump down onto a small stone below

and hold tight. I could see the ground and people far below, and Baby

Elephant with many people on and around, and the wind brought voices up

from there.

Grey already jumped down and was inviting me to join him waving his arm

as a circus trainer. He was saying something but I was deaf from fear.

Shall I come back? I didn't realise how I jumped and felt myself flying.

Hardly had I reached the solid surface, I saw Artist's long legs already

in the air above me and nicked to step aside to let him on the stone. His

was a perfect landing, and we continued.

I was writing this and thought that anybody might feel my stories

encouraging for hot heads risking to climb without stand by. Hopefully not,

however. The consequences of a fall are so vivid that no word can add

anything to the understanding of danger.

Attractive examples are dangerous where the danger is not obvious, say,

on slipping snowy slopes. These slopes seem so inviting at the first sight,

and a happy tourist enjoys a sunny day and, unaware, runs ahead straight

into a hug of the "white death". Thus, writing tales about

mountain skiing requires much caution.

I think taking risks at random makes no sense. This is the way of a

lazy body, - better to take a risk than walk around, - or of a lazy mind,

- better to hope for good luck than think. Those who risk blindly just

never set their will and skill against difficulty and danger.

Stable rocks where the danger is obvious are quite a different matter,

though sometimes people fall off …

The next day we set off to the Wild pillars. We were in a hurry as it

was late and getting dark and there were fifteen miles of the taiga ahead.

I was tempted to try the Wilds which was then unusual.

The guys, experienced mountaineers, were running like deer even talking

on their way. They were talking over mountains and hardships they met

during long walking trips. I was running along and my heart was beating

regularly and joyfully, but I knew much harder times. I learned once that

the only tough thing in a trip was to be the weakest, and the recovery

took three years. Fortunately my companions didn't know that.

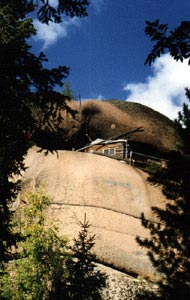

We arrived in the dark. It was unusual and terrifying to climb rocks at

night. At last we had reached the hut called Griffins, a timber hut built

on a ledge high up the rock of the same name. When building it, people

used a winch to lift the logs from the rock foot. The hut is very nice and

matches perfectly the rock architecture. It was a pleasure to get inside

the safety of a home and to sprawl on a wide plank bed after the night

climb. We arrived in the dark. It was unusual and terrifying to climb rocks at

night. At last we had reached the hut called Griffins, a timber hut built

on a ledge high up the rock of the same name. When building it, people

used a winch to lift the logs from the rock foot. The hut is very nice and

matches perfectly the rock architecture. It was a pleasure to get inside

the safety of a home and to sprawl on a wide plank bed after the night

climb.

I asked Victor Yanov, our guide, if the "genuine stolbists"

ever fall off. - "Not more often than expert mountaineers. They have

some inner feeling, some intuitive skill to calculate. A good climber

never takes up a route without feeling sure. There is a chimney leading

from below to Communard - a block on First Pillar - called Abalakov's (whether

it's true or not, they say Yevgeny Abalakov, the famous mountaineer, used

to do it once). The best climbers worked it using safety ropes, but failed.

And a guy nicknamed Simochka once tried it simply unroped and suddenly

found a way through. - Was he the most skilled climber? Who knows.

Simochka usually climbed smartly, without a least effort, and always

smiling. It was impossible for him to fall. He was a mechanic on a ship

and died elsewhere. I wrote down his name on Mitre." -

"Or Dusya Vlasova, she would have never fallen, had it not been

for one guest mountaineer from Perm who got stuck on Takmak. Although many

boys were staying at the foot, it was Dusya who set off for rescue as she

was the best climber. She was on her way up when the guy slipped off and

barged her down. Fortunately, it was not too high. The guy was hurt badly

however, but Dusya was lucky to only have broken her leg. In a week she

came to Stolby with crutches and thus climbed up First Pillar along the

Rolls. Then guys carried her to other rocks on their back."

I saw Dusya the day before. She was sitting on a stone beneath Second

Pillar. Grey gave her a smile and patted her short ginger hair. The guys

spoke about Dusya Vlasova as if everybody was supposed to know her.

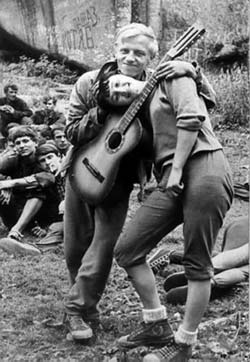

I used to know Dusya's elder brother, Victor, who had been a stolbist

since cradle and learned his ABC on the rocks. He was a lightsome climber,

always with his guitar on his back, climbing down the hardest routes head

first. He used to climb Communard with a samovar and firewood, made

pancakes up there and invited everybody to join him, though few were able

to do. He is known for a very generous person who would give away

everything he had to anybody. He could never fall off and people near him

never did. He used to live in the reserve weeks long picking mushrooms and

berries. He was nicknamed Gapon, nobody knows why. Six years ago during my

last trip to Stolby, I was sitting near a bonfire and saw a tall guy

emerged from the dark. I understood he was Gapon from the impression his

appearance produced on my companions around the fire. He sat aside and

kept off the talk, only sang a song about loneliness on the rocks.

I heard Gapon was taken for a governor of Stolby, but the guys told

that was rubbish. There can't be any governors or kings on Stolby as there

can't be majors among the majors.

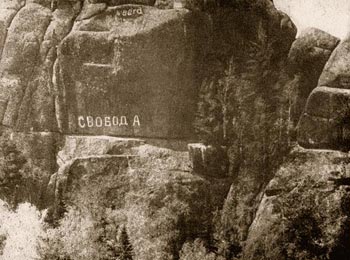

A wall on Second Pillar bears an inscription "Freedom", an

inscription with oil on a bare wall far from any possible routes. It has

existed since pre-revolution times but the letters are occasionally given

a fresh coat of paint and don't fade away. Before the Revolution people

put up red flags high on the rocks. Once somebody put up a flag on top of

Big Golden Eagle at night, though the rock is impossible to climb even in

the daytime. So, the police had to shoot it down from the ground. A wall on Second Pillar bears an inscription "Freedom", an

inscription with oil on a bare wall far from any possible routes. It has

existed since pre-revolution times but the letters are occasionally given

a fresh coat of paint and don't fade away. Before the Revolution people

put up red flags high on the rocks. Once somebody put up a flag on top of

Big Golden Eagle at night, though the rock is impossible to climb even in

the daytime. So, the police had to shoot it down from the ground.

It was Victor Yanov who told me the story. He's a professional artist

and made an engraving called "A flag on Golden Eagle". He told

people could climb the rocks even at night, for the routes are usually

short and can be memorised by touch. Stolbists often bet they can climb

the rocks even when blinded. There were veterans who had come blind from

the war but climbed by memory. However, climbing alone at night is

dangerous. Victor told he climbed Takmak in the dark when a boy and left

his knife on the top as a proof. Since then he has climbed Takmak solo at

night every spring for years just to make himself sure he's still young.

Big Golden Eagle is very hard to climb.

I have already told how I was climbing with Grey and Artist along the

easy and pleasant way of Rolls. However, I held back that the trip began

with an ordeal painful for my self-esteem. Now I feel liking to lay bare

how I tried to do Mitre. That happened not because I spent a sleepless

night on the plane or because I met a boy and a girl who had fallen off a

rock just before my arrival and I was carrying them on a self-made

stretcher. That time I came just to write about Stolby and to observe

myself in the acute feeling of risk. So I took up Mitre but suddenly asked

for a safety rope already in the middle of the way. Sergei Prusakov, an

expert climber patiently waited for me and tied the rope on my waist. I

continued my way up feeling excited and thinking about anything but the

route I was following when all at once I saw Sergei who took me over along

another route. Then he went up incredibly on a bare wall - I had never

seen anything like that before, I forgot we were on Mitre but just

wondered what he was holding on and what would happen.

That time I felt nothing special at the top. I went down to the safe

flat, again with the safety rope. Far below I could see green branches of

birches and cedars growing right from stone. Above on the wall I saw

Artist going down. Suddenly he mistook a cling hold and was obviously

stuck with his one leg unsupported and the other shaking menacingly.

Sergei spoke almost rudely, - "You, guy, hold on the cling and change

your legs! Don't be silly, or you fall!".

Artist found the cling holds, reached the fissure and put his hand

inside. Then it was something incredible that followed - he went up and

down again taking right the same way. - "That's it" - Sergei

encouraged.

Then we climbed Second Pillar along the Leushinsky route. That time I

climbed unroped, which is common on Stolby. We took a narrow gradually

opening chimney and I felt safer sheltered from the empty space around.

Sergei was nearby. His self-confidence seemed strange and even annoying.

Suddenly I thought by caprice - "What if I try to fall off? What will

he do?" Indeed, when going down, I was insolent to jump and felt my

foot slipping. Sergei stopped and explained firmly that my behaviour was

absolutely intolerable. That was how I understood the rules: to be as

careful as possible myself and the others will charge themselves with the

rest. Then we climbed Second Pillar along the Leushinsky route. That time I

climbed unroped, which is common on Stolby. We took a narrow gradually

opening chimney and I felt safer sheltered from the empty space around.

Sergei was nearby. His self-confidence seemed strange and even annoying.

Suddenly I thought by caprice - "What if I try to fall off? What will

he do?" Indeed, when going down, I was insolent to jump and felt my

foot slipping. Sergei stopped and explained firmly that my behaviour was

absolutely intolerable. That was how I understood the rules: to be as

careful as possible myself and the others will charge themselves with the

rest.

I thought then it was natural for a human to be extremely careful

otherwise the rashness may cost a life. Civilisation has spoilt people,

whereas they subconsciously seek to risk. However, bull fights would

sicken me, as well as fiercely competitive games, where malice is

inescapable. Rocks is quite a different matter.

I asked Sergei why, a professional mountaineer, he let beginners go

without safety ropes, and what he could do if somebody was slipping a

metre off him. "Actually the rope doesn’t matter" - he says, -

"I can spot when somebody is about falling and come up to give him a

hand." - "All people need, is a bit of support, a small effort,

because they hold perfectly by themselves".

Two days later I was leaving Stolby. I was walking alone along the

deserted path and stopped at Mitre to read once again the two memorial

signs on the wall “Vladimir Denisov, Sima, 1939-1962” and “Tsedrik

Alik, 1947-1968”.

Suddenly I thought I was leaving for Moscow and did not know when I

would be back. So it was very important for me to surmount Mitre, more so,

to do it alone. I set off, stopped at the swaying stone, sat astride it

and looked down. Finally I decided to continue and was about climbing up

… And - it started to rain. Climbing Mitra in the rain is absolutely

impossible and I met the rain as a salvation … |

|